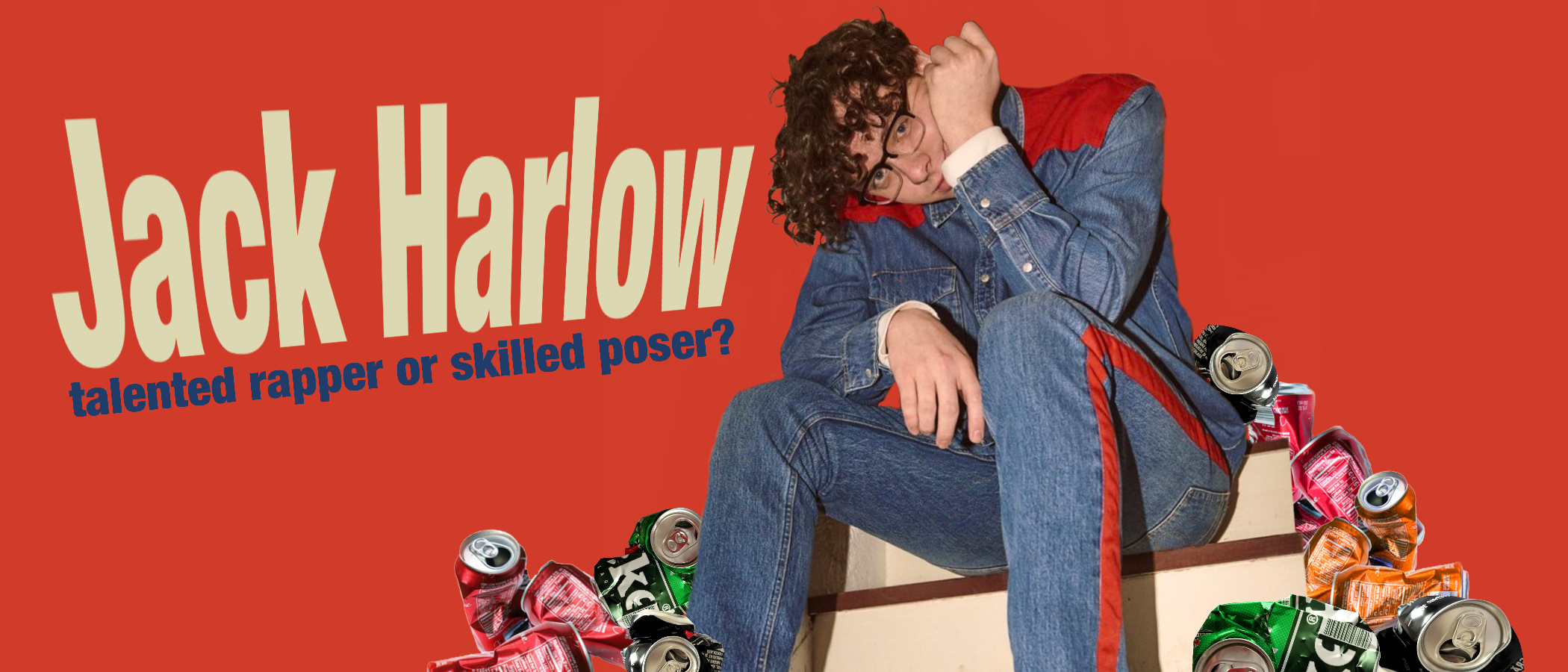

I've Heard One Jack Harlow Song—Read As I Decide If He's Actually Good or Not

By Nia Tucker

Jack Harlow’s name is immediately reminiscent of his major TikTok hit that has gained him his first ever Top 100 hit and features from the likes of legends like Lil Wayne. While his career started to grow before this, he’s been launched into the major spotlight and is receiving more accolades and attention than ever. A Stereogum profile of Harlow titled, “Jack Harlow Is Going To Be A Star, Whether Or Not He Ever Becomes A Great Rapper,” points to the industry problem of awarding stardom to mediocre white talent— particularly in the rap/hip-hop realm. It’s thesis is that although Harlow is not a great rapper, he possesses a star factor that gives him a pass. For those seeing him mingle among big hip-hop players and treat rap culture like a sandbox at recess, it’s frustrating to have white listeners especially, grant him a space within the culture. In order to determine if this space is well-deserved or just well-timed gentrification of culture in the age of TikTok, I explore his last two projects having had the luck of only hearing one song before this, but read below for a dive into some of the more notable tracks from his last two projects.

Confetti (2019) is actually Harlow’s fourth project but was the album that put him on the map. It’s not unique by any means but the singles are well-chosen, with “THRU THE NIGHT” featuring Bryson Tiller being a standout on the album. But throughout, there is a sense that whoever Jack Harlow is, is shrouded in Black culture. It reads as reiterated bars and melodies from rappers that have preceded him, and even the visuals for first track “GHOST,” and the aforementioned “THRU THE NIGHT,” feel like parodies of Black iconography, i.e. the classic roller rink and group shot with bottles popped and everyone posted up on top of cars.

The album itself is laced with AAVE (African-American Vernacular English) and working-class-turned-wealthy themes which feel “hip-hop” enough, but by a white rapper. And white rapper who cannot measure up to the Black rap features on this album nonetheless. There is no sense of Harlow’s story and no distinct sound that makes his music his. “WALK IN THE PARK” is a where he’s definitely more in his element. There’s no ostensible hip-hop play-pretend here—in the music video he’s a white boy playing baseball and doing what can be imagined white boys usually do. It’s almost reminiscent of early Mac Miller as the rapper-next-door, but there still feels like something is missing. His bars are evocative of those freestyle raps done in school cafeterias. The album wraps up with “RIVER ROAD,” the typical introspective, smooth type of rap monologue that nowadays Drake is known for, but again, Jack’s own language and style is missing. Generally, Confetti lacks a specified identity, if anything; the beats, old-school samples and aiding visuals are what carry his supposed talent.

Harlow’s first big hit is an amalgamation of a well-produced non-trap beat, easily captionable and memorable lyrics, and a flurry of AAVE. When people hear “WHATS POPPIN,” for the first time, one of two things are noted—“I thought he was Black!,” or, “This beat is really good. It’s a perfect recipe for a well-received album, and so, Harlow takes advantage and the following tracks of Sweet Action (2020) follow this same formula. “2STYLISH,” is a song/rap track that doesn’t have exceptionally distinct lyrics or production, but relies on the promise of catchiness and lyrics that would guarantee Harlow some major sing-alongs if he had a chance to perform at festivals. Nonetheless, aside from the main track that got him his fame, it possesses the most substance. Sweet Action’s tracklist doesn’t have a single song that is over 3 minutes—it’s very much a pre-game throwaway project. Harlow knows his audience—young, easily impressed kids not familiar with the traditions of hip-hop and the value of storytelling over an equally good beat. There’s no experimentation although now would’ve been the perfect landscape to do so as he rides off his internet fame. Tracks like “HEY BIG HEAD,” sound Bhad Bhabie-esque—hard, 808-heavy beats and Blaccent-tinged lyrics—and again, in the same vein as Confetti, the final track, “ONCE MAY COMES,” is a nostalgic, “we made it,” type song meant to have us embrace Harlow’s newfound success. There’s no sense of distinct malice or culture vulture-ness found in him as in other white rappers, but it’s hard to leave the project with a good taste in your mouth when there’s Black rappers—Bree Runway, Kari Faux, Cupcakke, just to name a few—that rap circles around him and receive nothing in return.

Jack Harlow doesn’t make the worst music in the world. There are worse rappers. But to suggest his talent is equal or above Black presence in rap today would be a lie. Having had gained a spot on this year’s XXL Freshman list, he pales in comparison to the far more melodic and sonically aware competitors alongside him. At the end of the day, what really makes good hip-hop can be boiled down to Blackness, and the inherent necessity of such to be able to create the genre and culture of hip-hop and rap. Harlow lacks all of that, which is exactly why he is able to top the charts. For white rappers like himself he is not measured by the same expectations of talent. It’s impressive for those looking to “invite someone to the cookout,” or that can flow lackadaisically over some, admittedly, really good beats. It’s why he has received a BET (Black Entertainment Television) nomination for Best New Artist, and why he was given space on the XXL list despite there only being two Black women alongside him in a year where Black women dominated every genre possible.

It’s clear that white artists, especially white men, are afforded leniency in their star power and talent. Consider this: if one has to be three Natty Lights deep to enjoy a track, is it truly good rap music?