Kendrick Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d city Turns Ten Years Old

Graphic by Lily Hartenstein

By Parker Bennett

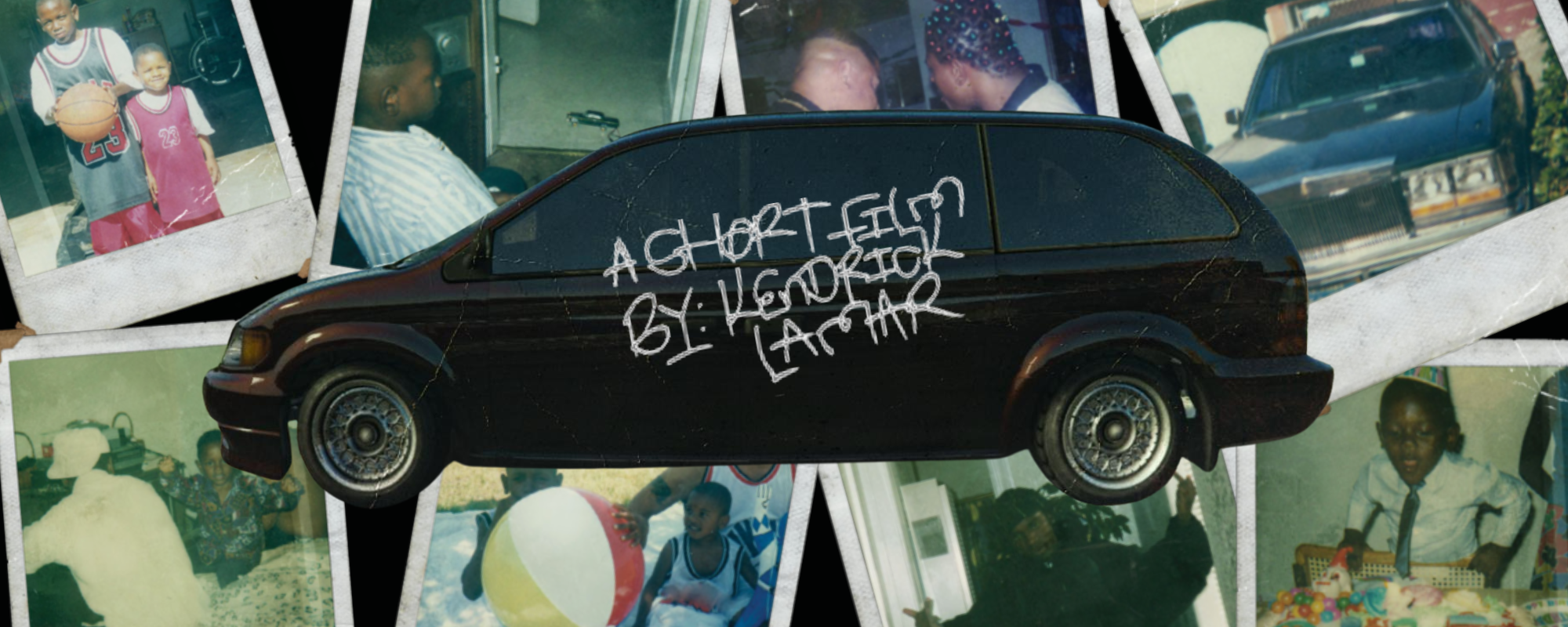

A maroon minivan, parked in front of a block of small Compton homes, framed by a cloudless blue sky and spiderweb asphalt, all captured on a fish-eye lens. It’s an image so indelible with music of the 2010’s that it almost feels counterintuitive trying to capture it in words. It’s an album cover that can be found on every record store shelf, seen in every hip-hop fan’s playlists, and displayed on nearly every Best Of list that came out that decade (including WECB’s!). It’s hard to believe, then, that this isn’t even the original cover art for Kendrick Lamar’s sophomore album good kid, m.A.A.d city, released on October 22, 2012—ten years ago today—and is instead the cover of the deluxe edition released in 2013.

This is all to say that both good kid and Kendrick’s status have grown to such astronomical heights that it feels impossible to recall the “before times”: before Kendrick was a household name, before good kid was being heralded as one of the greatest albums ever made, and before anyone knew what to expect when they clicked on a picture of a baby cradled by several faceless men (the original album cover) and first dove into the music within.

Calling good kid, m.A.A.d city impressive is an understatement. Since its release, good kid has yet to leave The Billboard 200 charts. No, you didn’t misread that. Since initially peaking at No. 2 in 2012, the album has stayed on the charts for ten years straight. Aside from that, it was the album that made Kendrick who he is today, and took him from the promising up and comer of Section.80 (2011) to the full-on king of hip-hop in the 2010’s. It’s an album that has lived with an entire generation of rap fans so indelibly that its name is now brought up in conversations alongside Nas’s Illmatic (1994), The Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready to Die (1994), and Outkast’s Aquemini (1998) as one of the greatest rap albums of all time. But how does it hold up in 2022, after a decade of success, hype, and even further achievement from Kendrick himself?

In many ways, relistening to good kid, m.A.A.d city feels like checking in on an old friend. From the first static-y crackles of a cassette tape popping into the deck and the voices of men mid-prayer coming to life, the stage is (re)set for a cinematic musical experience. As the subtitle for the album’s cover suggests, good kid plays very much like “a short film by Kendrick Lamar.” Over the course of the tracklist, the story of one night in an adolescent Kendrick’s (called K-Dot here, his original rap name) life is told, which travels through violence, tragedy, repentance, and growth.

Alongside the music, there’s a multitude of lo-fi skits scattered throughout the runtime which unfold the narrative in a non-linear fashion. These skits are incredibly well-written and acted, and introduce several key players to the album’s story, such as the femme fatale Sherane, K-Dot’s friend Dave, and Kendrick’s own parents.

The story begins with K-Dot taking his mom’s minivan to hang with his friends, and after a series of criminal activities, things spiral out of control when Kendrick is set up by Sherane and he and his friends are forced to come face-to-face with the cycle of violence in Compton. Ultimately, Kendrick is left with the choice to grow or stagnate from the trauma he’s endured, and portions of the album become ruminations from an older, wiser man looking back on what that choice has wrought for him. While the ambition to create such an involved and emotionally impactful narrative within an album is usually a distraction (see Logic’s The Incredible True Story (2015), the care Kendrick and his team put into the cohesion of this project makes it absolutely engrossing and deeply visceral.

At the time of its release, good kid’s singles were inescapable bangers that dominated airwaves, iPods, and meme compilations of the time. “Swimming Pools (Drank)”, “Bitch, Don’t Kill My Vibe”, “Backseat Freestyle”, and “Poetic Justice” were all staples of popular hip-hop in 2012, and gave Kendrick the boost he needed to go from underground sensation to certified hitmaker. The most impressive thing about all these songs, however, is how Kendrick was able to make such obvious grabs at radio play feel like integral and seamless aspects of the album. Take “Backseat Freestyle” for example, which is narratively framed as a freestyle between a young Kendrick (K-Dot) and his friends, and therefore allows for a raucous, high energy banger that satisfies a popular rap niche and still adds to the album’s overall experience. The same goes for “Swimming Pools”, which despite being one of the most heavily memed and overplayed rap songs of the Vine era still feels like a must-listen in the context of the album.

As time’s gone on, however, two songs have become unexpected sleeper hits that might epitomize the sound of good kid in 2022 more than the aforementioned singles. “Money Trees” is an incredibly addictive highlight that has gone from underrated fan favorite to one of Kendrick’s most streamed songs of all time. To this day, it’s still a head-bobbing, visceral experience, that transforms a Beach House sample into one of the most dreamy and hard-hitting beats in Kendrick’s catalog. Additionally, fellow TDE signee Jay Rock—who’s sadly faded into relative obscurity in recent years—delivers a performance that marks the only time in Kendrick’s entire career that he’s ever been washed on his own song. (“Take your J’s and tell you to kick it where a Foot Locker is.”)

“m.A.A.d city” marks the other sleeper hit from this project, and the appeal is easy to see. This song is a tour-de-force of excellence that embodies the duality of Compton through Kendrick’s eyes: a violent, drug-infested landscape that suffers under the weight of poverty, but also a vibrant home that holds some of the most important Black history in America. The song’s first half—inarguably the more iconic portion—was at one time the go-to “hard” rap song for meme compilations and edits, but still holds up with one of the most high-octane and lyrically dense moments in hip-hop history. The ferocity of this intro is so intense and so instantly identifiable that it’s no surprise that many rap fans (and even Kendrick fans) are still caught off guard by the song’s second half. With an unbelievably good MC Eiht feature and a melodic and lyrical re-interpolation of Ice Cube’s “Bird in the Hand”, “m.A.A.d city”’s second half is arguably the most certifiably West Coast moment of the whole album. It’s a sonic journey through the back-alleys of hip-hop’s favorite hood, told with the precision and sympathy that only a survivor of that environment could ever portray.

And then, there’s “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst”. For those who have never heard this song, it’s difficult to convey just how masterful every single aspect of its construction is. For many, this is the definitive apex of Kendrick’s career, and that’s a pretty hard assertion to argue. On a full listen of good kid, m.A.A.d city, “Sing About Me” feels like the conceptual heart of the project, and is almost always the site of the most memorable takeaways. The beat is a soft backdrop to some of the most tightly written and deeply poetic lyrics of not only Kendrick’s career, but the entirety of songwriting history. It’s 12 minutes of goosebump-inducing effect, and relistening to it for this review—probably my 100th time hearing the song—it still brought tears to my eyes. For anyone confused as to what exactly makes Kendrick so great, why his fans are avid for his music, why he’s consistently held up as one of the most important voices of this generation; “Sing About Me” is the definitive summation of what makes Kendrick one of the most captivating MC’s to ever do it, and getting to listen to it still feels like a privilege to this day.

After ten years, good kid m.A.A.d city’s status as legendary hasn’t lessened any of its impact. No matter how many times you’ve heard it, no matter how often it’s been brought up in classic album conversations, it still manages to ensnare every part of the listener for its hour-long runtime. In 2012, it was hard to imagine the heights Kendrick Lamar would reach in the future of his career. However, as someone in 2022 looking back to where it all began, good kid reads like a road-map of everything that would come to define modern rap’s golden child, and the monumental impact he was going to have. Here’s to one of the greatest albums of the past ten years, and here’s to the immense pleasure that is knowing that this same conversation will still be in effect in 2032, and every conceivable landmark for the foreseeable future.