Why I Loved to Gatekeep

Graphic by Mo Krueger

By Stephanie Weber

My sophomore year of highschool, a friend asked me what I was listening to, and I responded “Oh, you wouldn’t know the band,” thinking I was so cool because I was listening to a band he didn’t know. I showed up my friend, feeling better about myself because I knew something he didn’t. This wasn’t a new experience; I had been gatekeeping music for years.

My pride for niche Spotify playlists and obscure bands started way before high school. Despite her gatekeeping efforts, I stole my sister’s music taste around 12 years old, defining my taste with bands like Two Door Cinema Club, Vampire Weekend, and Vance Joy. With my trusty Pandora app in hand, I entered the world of music discovery, finding new “niche” bands every day. As I came into young adulthood, I tried to find originality everywhere—in my clothes, makeup, extraversion, and above all, in my music. I became the most insufferable music fan ever. I began to gatekeep the most popular artists, holding the pride of my musical supremacy close to my heart. Although everyone alongside me knew all the words to Panic! At The Disco’s “Death of A Bachelor” and was listening to Lorde’s Pure Heroine, I still thought I was original.

It was quite a shock, then, to enter Emerson College — the home of individuality. Meeting people is hard, but proves to be especially difficult at a school and community that prioritizes creativity and distinguishing yourself from others. I quickly realized that the façade of trying to be cool and mysterious, and charming peers with knowledge about niche films and the local music scene is appealing for the first week or so, but gets old fast. I thought my minute knowledge on popular music movements like RiotGrrrl and ‘60s Britpop would garner me this attention too, until I realized that there are other people who have more knowledge than me, people who’ve been listening to music since they were three, playing self-composed songs on a guitar that’s been passed down between generations, or were otherwise far more original than me.

As I’ve gotten to know more people, I’ve observed that there are two groups of people who love music. The first is a group defined by enthusiasm—for them, talking about a band, whether big name or underground, is exciting. They want to know everything there is to know about the musicians they like. Ultimately, they like to share music with people. The second group is notoriously defined by being gatekeepers, sometimes referred to as “male manipulators.” They love to mansplain what midwest emo is and provide names of bands you’ve never heard of and won’t care to listen to in an effort to prove their creative supremacy. They make you feel inadequate for not knowing the entire history of Fugazi or the ins-and-outs of music production.

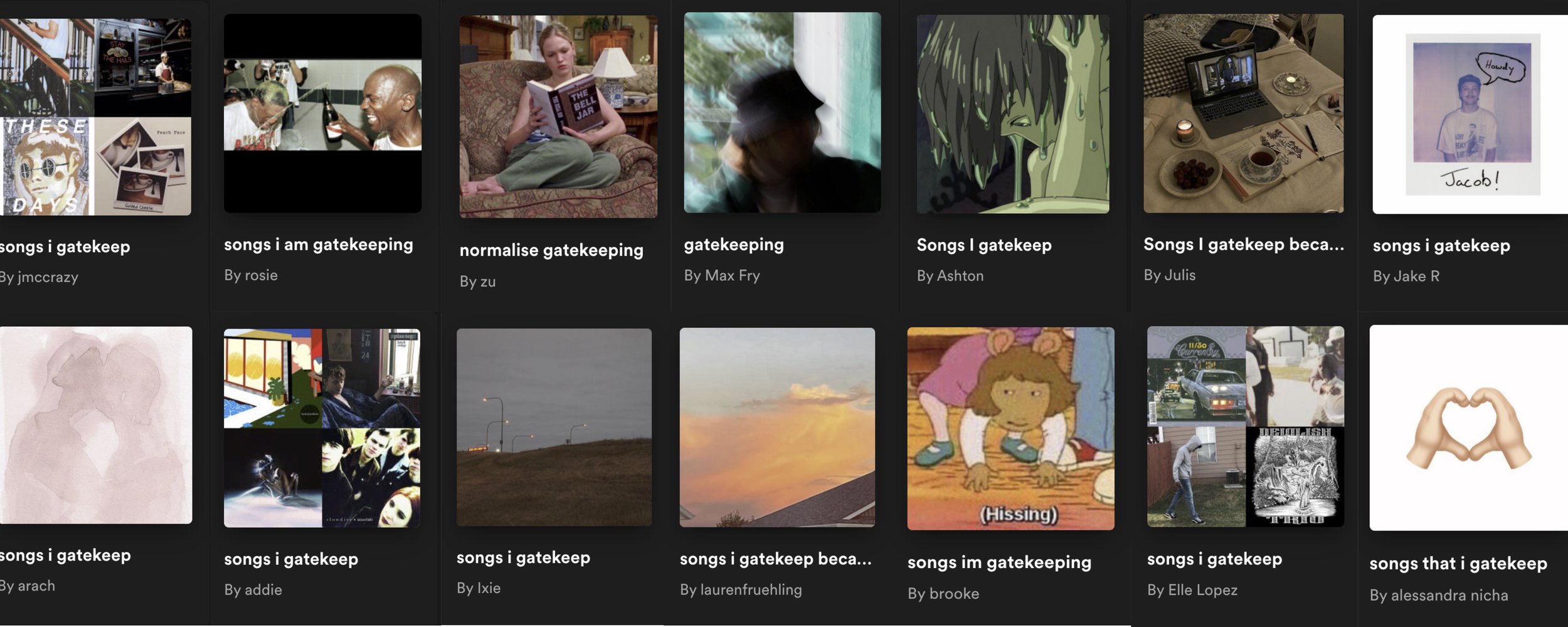

I was recently asked what my red flag is. I answered something fairly banal, but I should have said that I used to gatekeep and belonged on the margins of being a non-toxic male manipulator. I have a meme saved in my phone that reads, “did it hurt when the song you were gatekeeping finally got mainstream?” The answer is yes. There is something so personal and intimate about keeping a song to yourself, tending to it like a secret, and streaming it so many times it feels sacred. The same goes for artists—sometimes I feel like an artist is personally singing to me, writing lyrics that are so deeply connected to my life it’s uncanny. Yet, a lot of listeners feel like this, and like me, are longing to feel unique and individualistic in a society that seeks to homogenize. I used to gatekeep music because I wanted to feel special. I wanted to feel like my life had meaning beyond the superficial image I presented. Gatekeeping was a tool to do that; it’s a way to claim something personal in a world of inane similarity. Telling people you have a 100 percent rating on Obscurify elevates your cool status, legitimizing not only your knowledge but your existence.

When music, particularly very special music, is shared, it becomes a very real lived experience; you’re now bonded with someone and share a memory together. Even when bands have millions of listeners, gatekeeping still continues because of the concept of being a bridge. When I introduce someone to a new band, or make them a playlist, I do it from a place of love and giving. I want to be a bridge that connects this person in my life to me, and putting them onto the music I identify with is just the facilitation tool.

Over the last couple years, I realized I was annoying for gatekeeping, and finally stopped doing it. Part of it had to do with being on TikTok and the “trendification” of music. Being bombarded with new songs every ten seconds altered something in my brain to consume music differently. Every year, my Spotify wrapped numbers increase because of how much music stimulation I need. TikTok also introduced me to countless bands, artists, genres, music movements, and people in the industry who are all doing really cool stuff. If other people weren’t sharing their music, I wouldn’t know about it either. I realized that I love music and it should be shared with everyone, otherwise the deep cuts are there just for the elite few. Sharing music is empowering, and in a digital landscape, should be accessible for everyone.

Gatekeeping is not a dying art, sadly, but it’s the job of music lovers to resist it. Music was created for unity and community, not to be weaponized. It’s cheesy, but sharing is truly caring. Moral of the story: share your music with everyone. Send that Amy Whinehouse deep cut only found on YouTube with your new lover, but also share Radiohead’s Pablo Honey even though “Creep” has trillions of streams. Surround yourself with music and share it unapologetically without being asked.