Is Riot Grrrl Dead?

by Mara Tatevosian

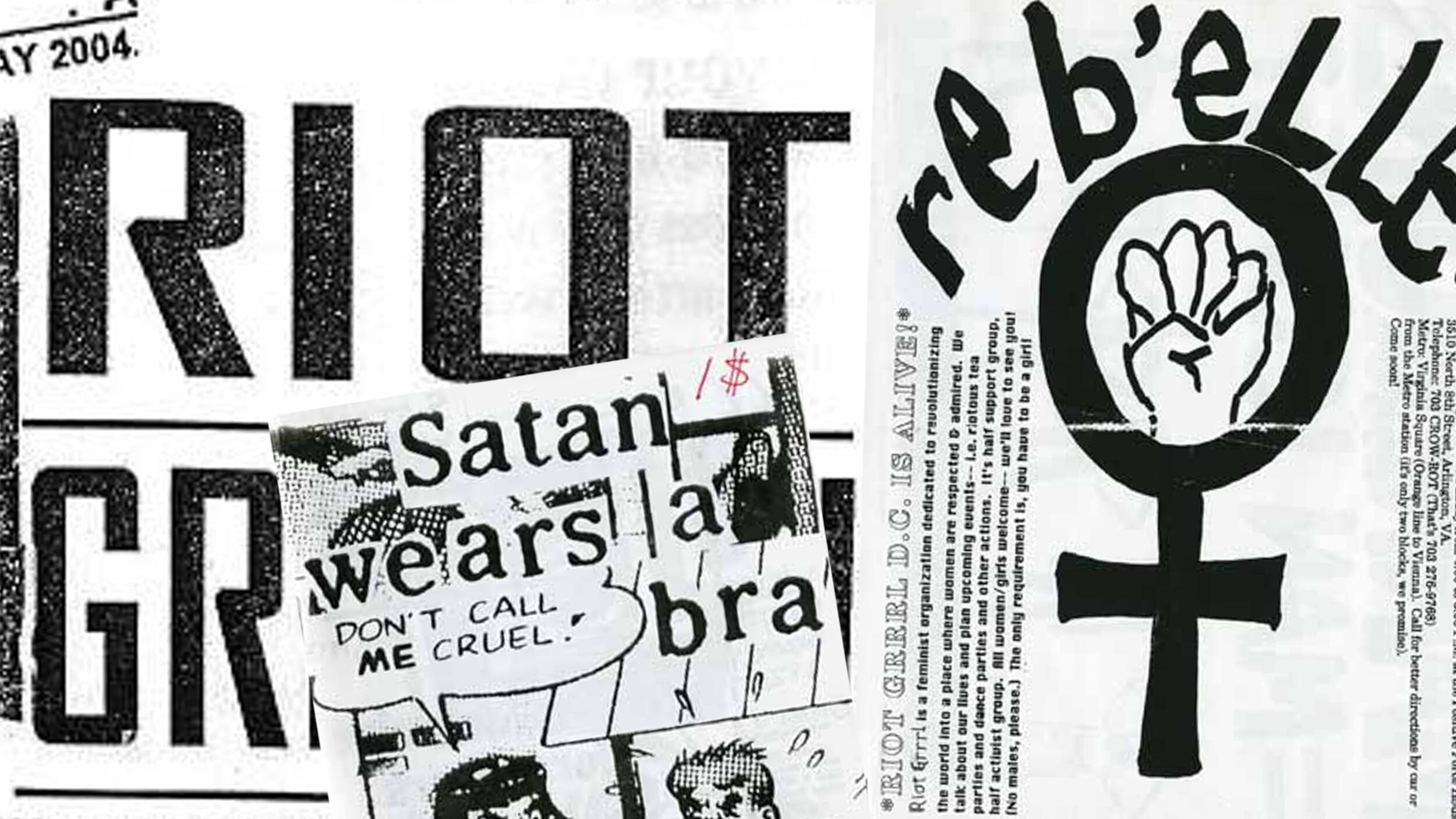

In 1991, a group of young women at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington held a meeting to discuss sexism in the punk scene. Reaching backward through punk’s history, women were treated like novelties. Bands like the Sex Pistols and the Ramones have taken their place as cultural touchstones in music, while their female counterparts like the Slits and the Raincoats have descended into obscurity in mainstream outlets. The mistreatment of women in punk escalated in the ’90s and eventually, the women grew tired of being ignored. Thus, came Riot Grrrl. By choosing not to adhere to societal constructs placed on gender identity, Riot Grrrls brought attention to uninhibited female anger for the first time — and through consciousness-raising protests, the movement spread beyond the Pacific Northwest across America. With the creation of the new woman, came their manifesto that pushed women to create their own music, zines, and media, due to the lack of space for women in the existing ones.

In an attempt to co-opt sexism, bands like Bikini Kill, Bratmobile, Heavens to Betsy, and Team Dresch wrote descriptive and indignant songs that weighed on topics like rape, racism, depression, and homophobia. Because the movement was a claim to autonomy, Riot Grrrls were very vocal about their disdain toward American politics as well.

But by the late ’90s, “girl power” was appropriated by female pop groups like the Spice Girls. Many fans claim that this ended the movement because the commercialization of feminism created a narrative that subconsciously catered to men. I disagree.

It’s difficult to say that Riot Grrrl ended in the late ’90s because the women of the movement, particularly of the music, didn’t stop their careers. Only two years after Bikini Kill’s last album in 1996, frontwoman Kathleen Hanna formed Le Tigre with Johanna Fateman and Sadie Benning (who was later replaced by JD Samson). Bratmobile’s Allison Wolfe joined Cold Cold Hearts and Partyline. Team Dresch’s Kaia Wilson and zine maker/photographer Tammy Rae Carland formed Mr. Lady Records. Most notably, Corin Tucker of Heavens to Betsy and Carrie Brownstein of Excuse 17 formed Sleater Kinney near the end of the original movement and released 7 studio albums at a consistent rate until 2006.

As they moved towards a new century, these women moved beyond some of the original Riot Grrrl objectives like boycotting record labels and ignoring mainstream media. Ambition beyond a movement isn’t criteria for an end, it’s merely the reshaping of one.

By leaving Olympia, WA, Sleater-Kinney went on to tour the world and eventually open for Pearl Jam. Le Tigre continued to make political music with a different sound and reached a wider audience. Bands like The Gossip and Pussy Riot continue to make music that follows the Riot Grrrl code.

One could argue that the Riot Grrrl movement was pronounced dead in the late ’90s, but surely, the Riot Grrrl mentality remained. It may have been inconsistent with its anarchical and leaderless roots, but angry politics continued to inspire the music that came after. In her book Girls to the Front: The True Story of the Riot Grrrl Revolution, Sara Marcus makes an interesting sentiment about the influence of Riot Grrrl, particularly focusing on accessibility to the movement. Because Riot Grrrl was ostensibly a geographically limited movement, many women didn’t gain access to bands like Bikini Kill. And there are younger women who blindly listen to female artists that came after Bikini Kill without the knowledge of their influence.

Marcus explains that “we’re at a third-generation degraded copy, and at the same time, there’s an embrace of anger and obscenity that does something for people. Even the Spice Girls are like a fourth-generation degraded copy from Riot Grrrl. So, a lot of the effects happened firsthand, secondhand, thirdhand, fourth hand.”

Until the late 2010s, young women who reached backward towards Riot Grrrls had no means of seeing them perform; at that time, the movement’s definitive bands were gone. If Riot Grrrl died in the late ’90s, it was never replaced by another movement; rather, the essence of the movement lived on in the spirits of fans and contemporary musicians who found themselves in the music decades later.

Today, however, classic Riot Grrrl persists with the acts that started it all. In 2015, Sleater Kinney announced the release of their album, No Cities to Love, after a decade long hiatus and are currently touring with their newest album, The Center Won’t Hold. On January 15th, 2019 – nearly 3 decades after Riot Grrrl’s genesis – Bikini Kill announced their return. In June of 2019, Team Dresch released their first new song in two decades and toured the US. With three of the biggest Riot Grrrl acts making a resurgence, the question of Riot Grrrls’ shelf life returns. And with this return, came the question of evolution – what changes were Riot Grrrls going to make to fit with the new, intersectional feminism of the 20th Century?

It’s no accident that these bands reunited after Trump’s election and are just as vocal in their criticisms as they were of Bush and Clinton in the ’90s. Perhaps it takes drastic measures for Riot Grrrls to reassemble and demand action. The reawakening of original Riot Grrrls made a larger attempt to reshape the original narrative that insisted Riot Grrrl was a white movement. In their tour lineup, Bikini Kill included Alice Bag, a Mexican American punk singer and educator from East LA. Bag was a large power in 70s LA punk but her influence seems to be ignored in music history. Newer artists like Kaina and Shamir joined Sleater Kinney on their most recent tour and had Lizzo as an opener in 2015. Kaina is a first-generation Latina R&B singer and Shamir is a black musician whose music falls in between indie rock and electronic. The one thing these musicians have in common is politics and the hunger to defeat oppressive powers – which in its essence, is Riot Grrrl.

As someone who spent her youth dwelling on the fantasies of this movement, it’s interesting to take part in its resurgence. This newfound access to Sleater Kinney, Bikini Kill, and Team Dresch has opened a dialogue on whether we are merely fans or vessels for the movement’s future. There is validity in bands like Bikini Kill and Sleater Kinney moving beyond their buoyant anger of the ’90s because Riot Grrrl remains in the presence of youth. Since the original Riot Grrrl rage remains present in the genre’s music, young women continue to identify with it, and incidentally, fall into the cyclical nature of Riot Grrrl. The important facets of this movement fed into the musical movements that came after – like current DIY bands with feminist intentions and even musicians beyond indie rock.

Riot Grrrl isn’t dead—it’s just reshaping and changing in relation to how feminism is. The original Riot Grrrl was evidently a white one and its resurgence gives an opportunity to evolve the movement’s original antics. Even if we are taking part in a fifth-hand degraded copy of what once was, Riot Grrrl can’t be dead because women remain adamant about expressing their rage.

My daughter has been on this path for many years, she has a determination about her.

LISTEN TO MY BODY. MY CHOICE. HERE!! : http://hyperurl.co/PL-MyBodyMyChoice

LYRICS :

so you think you know better than me

think I’m less just cause I bleed

you shouldn’t bite at the hand that feeds

I’m not here to satisfy your needs

so you think you know better than us

just cause life’s given you a step up

we’re loud and proud picking up a fuss

your gender roles are ridiculous

MY BODY MY CHOICE

MY LIFE MY VOICE

MY BODY MY CHOICE

MY LIFE MY VOICE

so you want to dominate

oppress minorities with mindless hate

we’re not that easy to indoctrinate

you wanna rule but you’ll have to wait

so you wanna be the ruling class

get through life with your free pass

inequality cannot last

so shove your archaic views up your arse

MY BODY MY CHOICE

MY LIFE MY VOICE

MY BODY MY CHOICE

MY LIFE MY VOICE

NO SYMPATHY FOR THE RAPIST

NO SYMPATHY FOR THE ABUSER

NO SYMPATHY FOR THE RAPIST

NO SYMPATHY MY BODY MY CHOICE

MY BODY MY CHOICE

MY LIFE MY VOICE

MY BODY MY CHOICE

MY LIFE MY VOICE

MY BODY MY CHOICE

MY LIFE MY VOICE

MY BODY MY CHOICE

MY LIFE MY VOICE

def agree !!! riot grrl never died, if evolved.

agreed! it never died. there is a very active riotgrrrl community online (especially on instagram) of young grrrls/ghouls making zines and music. i love being a part of this community and watching it transform into a more inclusive and understanding movement than the 90s held. sending love to my fellow grrrls & ghouls <3

hey cassie could u link some riot grrrl accs?