Broad Strokes: A Quick Breakdown of Music Implementation in Film

by Isaiah Anthony

Recall Star Wars (1977); the final scene, specifically. A grand ballroom; endless rows of generic soldiers; the heroes in gaudy jackets, walking down the aisle, receiving medals to roaring applause.

In that last scene, the grandiose resolution to a film that shows little notions of subtlety, the filmmakers made a fascinating decision that not only saved the scene but set the stage for the cultural phenomenon that the film would become.

There is not a single line of dialogue between the heroes of Star Wars. The audience is spared from congratulatory speeches, one-liners, and quips about being a long way from home. In terms of storytelling, this practice in restraint is one of the smartest decisions made in Star Wars.

Without the burden of dialogue, the scene yields near complete sensory power over to the strongest aspect of Star Wars – the music.

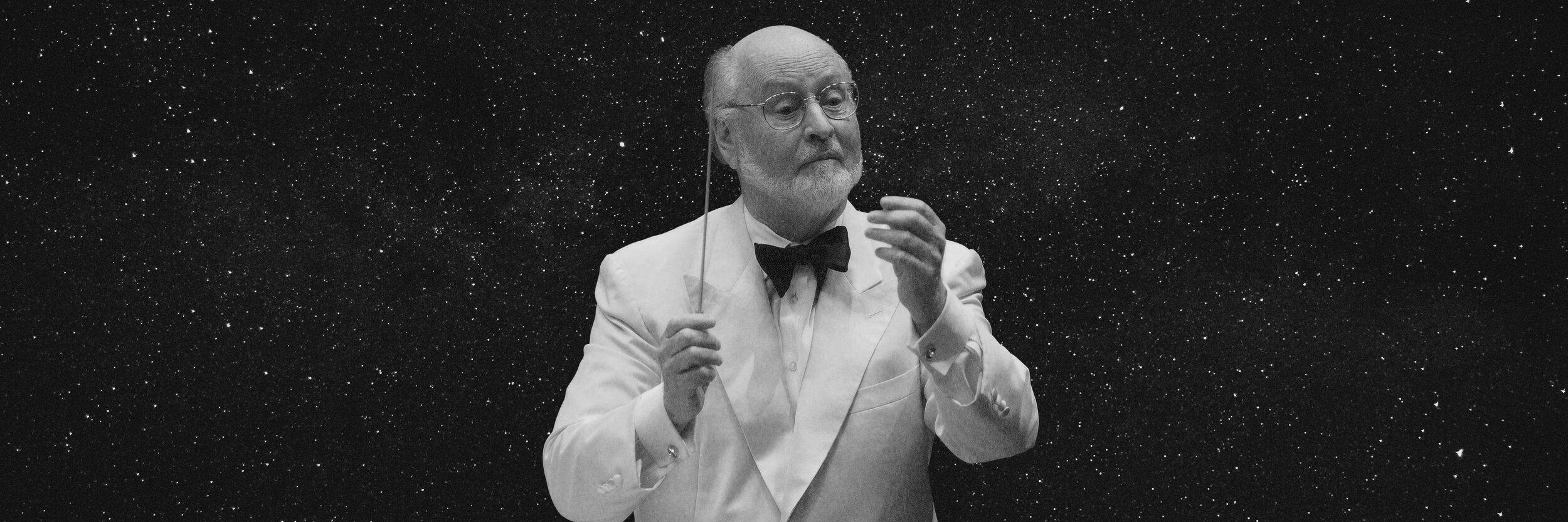

The audience is enveloped in the now-iconic John Williams score. Trumpets blare, cymbals smash, violins swoon in harmony to give the scene an emotional ambiance perhaps greater than the sum of its parts.

At the intersection of music and film, the ideal result is a symbiotic relationship that elevates both products of their medium. The audience should never again be able to hear a song without thinking of a moment in a film or think about a movie without humming a relevant underlying song.

This is not a simple task – it’s a tightrope between the cliffs of subtly and bravado. Lean too far towards subtlety and the message is lost on the audience, too far the other way and it feels like a crutch, compensating for the weaknesses of the movie, which, for some of the following cases, is apt.

In the best-case scenario, the film and the supplementing music seamlessly work in tandem, elevating the combined artistic product into higher levels of cultural significance while simultaneously standing on their own.

Now take the conclusion to 2001’s Ocean’s Eleven. The heist is over and the crew got away clean. As they relish in their victory, they stand peacefully alongside the Bellagio casino fountain, perhaps pondering what to do next. One by one, the members depart – slowly, as if hesitant to leave behind the comradery built from their individual greed. All along, they are serenaded by Claude Debussy’s “Clare de Lune.” The film’s jazz-heavy score created a chaotic, but meticulously arranged energy to the film which perfectly complemented the characters and story, but in the final moments, that all dissipates in favor of a slow, peaceful melody escorting the audience to an unparalleled sense of catharsis.

“Clair de lune”, composed by Claude Debussy, in Ocean’s Eleven. One of my favorite parts.

Debussy published “Clare de Lune” in 1905, nearly a century before director Steven Soderbergh began work on Ocean’s Eleven, and yet the piano melody feels made with a Las Vegas heist in mind. Ocean’s Eleven was not responsible for the creation of “Clare de Lune,” but its beautiful integration has still resulted in countless frustrated pianist fielding requests to play the Ocean’s Eleven fountain song.

As covered above, an original score has the potential to raise a film from simply a ‘film’ to a ‘fundamental piece of society and media.’ The impact that composers such as John Williams and Hans Zimmer have had on the mainstream culture of the past half-century is unrivaled.

When done well, original soundtracks are not exclusive to orchestral productions. Take Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (2018). The film’s original soundtrack was composed of hip-hop heavy tracks made by current artists, and they did a lot for the film, both tonally and in the character development of the protagonist. This is most clearly demonstrated with the opening scene depicting young Miles Morales struggling to sing along to Swae Lee’s mumbled verse on ‘Sunflower.’ And while these songs were made for the film, they had the legs to exist and succeed independently, with ‘Sunflower’ going on to top the Billboard music chart.

Watch the official ‘Miles sings Post Malone Sunflower’ clip for Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse, an animation movie starring Shameik Moore, Liev Schreiber and Hailee Steinfeld. In theaters December 14, 2018. A big-screen animated take on Spider-Man featuring Miles Morales, an Afro-Latino New York teen who is endowed with amazing powers similar to those of Peter Parker after a bite from a genetically engineered spider.

In recent years, a new method of using music has risen to cultural prominence. In this approach, the music takes on a much more overt role in the film, using preexisting properties that are well known to audiences. Popularizers of this phenomenon include most notably Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) and Baby Driver (2017). In both films, the music is framed as the ‘personal soundtrack’ of the protagonists, with both characters having their music player as a key aspect of their persona. While there is a charm to this merging, the gimmick is quickly running its course.

This leads to the highest-risk, highest-reward intersection of genres — films about music.

Bohemian Rhapsody was nominated for ‘Best Picture’ at the 2019 Academy Awards. It nearly won one of the most prestigious awards in the industry and made just shy of $1 billion dollars at the box office on a budget of $50 million. The movie did alright for itself.

And yet, Bohemian Rhapsody is a bad movie.

To rationalize its success, first, strip the movie down to its core themes. Remove all mentions of the band Queen and its eccentric frontman. Replace Queen’s music with vague 80s rock. Doing so leaves a story of a band that achieves fame, starts to fight, breaks up briefly, then gets back together to play “The Big Show.” Perhaps this rationale can be applied to deconstruct and oversimplify any film, but not every film is as shallow as this one and approaches source material from such an egregiously ingenuine framework.

Bohemian Rhapsody is no different than the countless band-focused films that have hit theatres. The variable that separates Bohemian Rhapsody from the pack is the music of Queen and the name recognition of Freddie Mercury. That’s what sold tickets and turned heads during award season.

The iconic music of Queen did not make the story of Bohemian Rhapsody better. It simply served to distract the audience from the film’s shortcomings. To its credit, it worked.

This is the most malicious of the cohesion of music and film. The music is the skin of a hollow body, with mass-marketing and appeal placed at the forefront of production.

The impact that music has on film storytelling is immeasurable, and when properly implemented can be the catalyst for moments of immense beauty, drama, and weight. This cohesion is an elevation of emotion at it’s best and a cheap appeal to preexisting interests at it’s worst. To all filmmakers credit, beautifully done or botched, music certainly makes for a memorable scene.